Remixed to Relevance

The U.S. Open's radical revamp of mixed doubles breathes new life into a failing format.

A version of this story also appears at The Second Serve, a weekly newsletter covering pro tennis and the fashion and culture adjacent to it. Sign up here!

It seems silly as I admit it now, but when I first started in earnest as a full-time traveling reporter following the tennis tours in 2012, one of the things I genuinely was most excited about covering was mixed doubles.

The ways the sports and cultures of men’s and women’s tennis combine, contrast, and clash on tour had always been of interest to me; mixed doubles was the unique crossover moment for the characters and storylines from the two respective tours to collide, face-to-face, head-to-head, in a bona fide competition, laden with its own unique strategies and etiquettes.

A New Hope

The time seemed right in 2012, I had figured, for a mixed doubles renaissance: Olympic tennis was adding a mixed doubles event to the program in London that year, which I was sure would add new energy and recognition to the often-overlooked format. Mixed doubles was ripe for elevation it had never achieved before.

So when I began planning my first overseas trip to cover tennis to begin the 2012 season in Australia, the first tournament I booked was Hopman Cup, the unique mixed-team event in far-flung Perth. There was a great field with lots of singles stars there, and lots of talk about the Olympics’ addition making mixed doubles a priority for the game’s best like never before. Early returns Down Under were hugely promising as January 2012 wore on: a couple weeks later in Melbourne, the most buzzworthy Olympic preview pairing possible—American singles superstars Andy Roddick and Serena Williams—entered the Australian Open mixed doubles draw together. The addition of mixed doubles events at big ATP-WTA tournaments like Indian Wells and Miami was being discussed as an obvious likelihood.

But it didn’t take long before the sizzle turned to fizzle. Roddick hurt his leg in his second round singles loss to Lleyton Hewitt and withdrew from mixed doubles; he and Serena never entered a tournament together anywhere else ever again. Indian Wells and Miami—and the various other combined tournaments—didn’t add mixed doubles after all, however obvious it might have seemed. The 2012 Olympic mixed doubles event at Wimbledon was pretty great, as it happened—Belarusians Victoria Azarenka and Max Mirnyi beat the home team of Laura Robson and Andy Murray in a nail-biting gold medal match—but it proved to be a one-off that did nothing to keep the format warm once the Olympic flame was snuffed out.

Left Behind:

In the 13 years since, while tennis as a whole has grown by various metrics, particularly at the Grand Slam events, the mixed doubles there has stagnated, through both neglect and disinterest.

This is most easily quantified in prize money, where mixed doubles has been been increasingly shortchanged amid raises elsewhere.

A mixed doubles champion back at that 2012 Australian Open got A$67,750 for a win, which was more than a player got for reaching the third round of singles (A$54,625) at the time. In 2025, the mixed doubles champion’s prize money has barely crept up to A$87,500 dollars, while the third round singles prize money has more than quintupled to A$290,000. Now you get significantly more (A$132,000) for losing in the first round of the singles main draw than you do for winning the entire mixed doubles competition.

Prize money, still, is the best indicator of value in tennis, and mixed doubles—which also doesn’t award any ranking points, uniquely among draws at majors—has been considered more or less worthless. The clout on offer has been low, too, and mixed doubles results have been irrelevant. Can you recall the names of the pair who won the 2025 Australian Open mixed doubles title just three weeks ago? Even if you’re a big tennis fan—based on a quick survey of many colleagues and tennis fan friends—I’d assume you already cannot1.

It’s undeniable, I think, that mixed doubles at majors, has operated at a low altitude that’s far from its potential. And it’s a tremendous shame, too, because mixed doubles should be an enormous asset for tennis, especially at the biggest tournaments on the calendar. All sorts of Olympic sports—archery, curling, judo, sailing, shooting, swimming, track, and more—have contrived newfangled mixed formats in recent years because of how dynamic and appealing mixed gender competitions are considered to be. Tennis, meanwhile, was invented with mixed doubles already at the forefront: one of my favorite factoids is that when Major Walter Clopton Wingfield published the first set of lawn tennis rules back in 1873, the lone illustration in the rulebook depicted a mixed doubles match.

But in tennis, mixed competition has mostly been stalling. But, significantly only ‘mostly’.

Star Attractions:

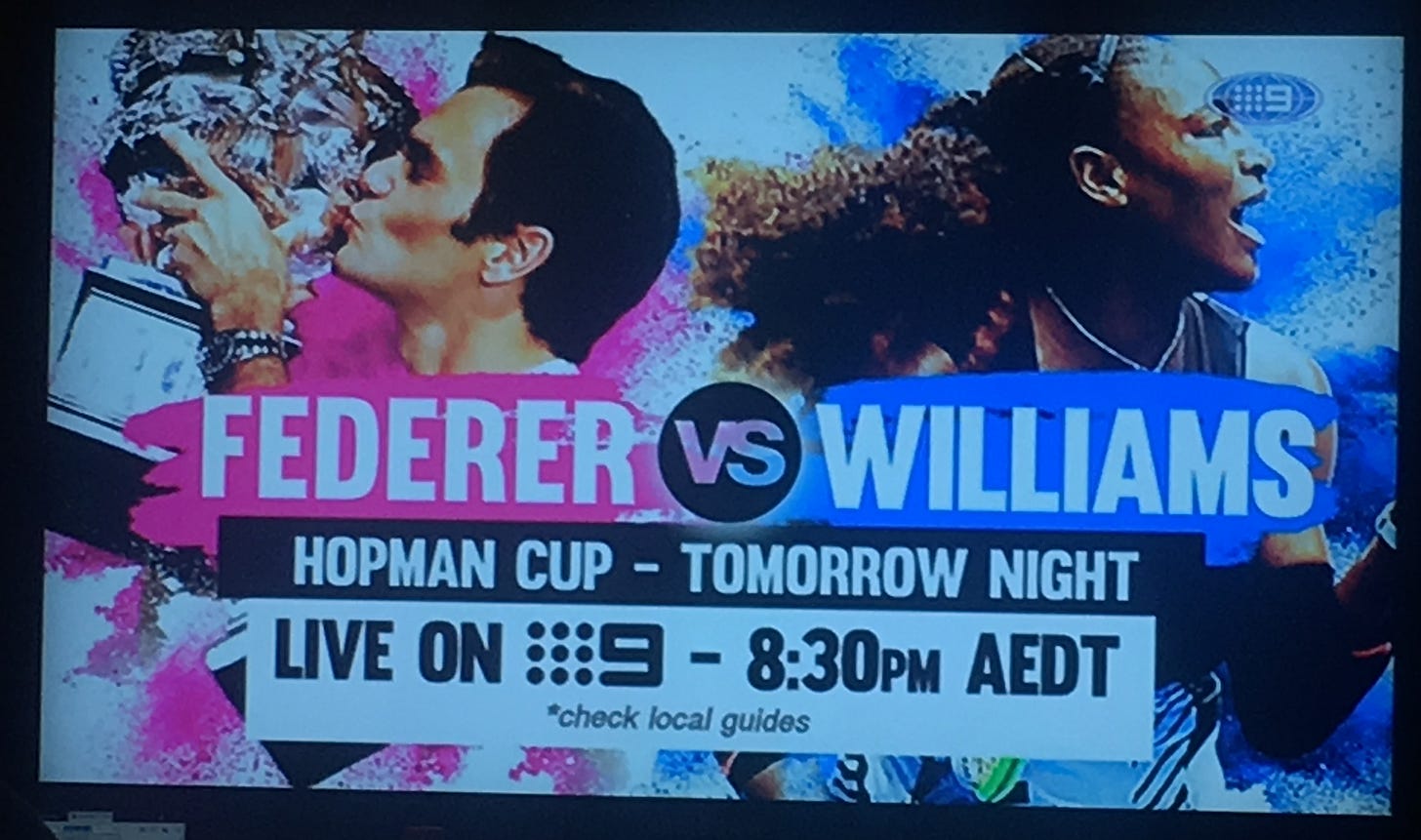

Mixed doubles has found a few undeniable moments in the spotlight: when there’s been top men’s and women’s stars competing on the same stage. I returned to the Hopman Cup in 2019—the final edition of the event in its original Perth locale—not out of general interest in mixed doubles, but to see the highly anticipated mixed doubles match pitting the Swiss team with Roger Federer against the American team starring Serena Williams.

It was the once-in-a-lifetime occasion that those two G.O.A.T. candidates ever shared a court, and it proved entirely worth the long trip; a photo of the two and a blurb of my article appeared the next day on the front page of The New York Times.

The other big moment that mixed doubles has had in the last decade happened that same year, coincidentally, when Serena entered the 2019 Wimbledon mixed doubles draw with Andy Murray. The pair played their first two matches on Centre Court, showing just how big an attraction mixed doubles could be when the stars opt in.

The only memorable mixed doubles that happened last month wasn’t at the Australian Open, but instead in the United Cup, where top stars like Iga Swiatek and Casper Ruud squared off, weeks before the year’s first major began.

It’s evident what makes the public care about mixed doubles: the participation of singles stars. It’s that simple.

A Population Apart:

But as singles stars opted out over and over, doubles—both same-gender and mixed doubles—has increasingly been the domain of an increasingly separate population of players: doubles specialists.

Only about a third of the Top 50 in the WTA doubles rankings (17 players) are also current Top 100 singles players. On the ATP side, the populations barely overlap at all: the Top 50 in the ATP doubles rankings contains just one current Top 100 singles player, Jordan Thompson. You have to scroll all the way down to No. 74 on the ATP doubles rankings, Sebastian Korda, to find the next Top 100 singles player.

This isn’t what was ever intended in tennis when tournaments first offered both formats together; doubles used to be another occasion to see the biggest stars competing and thriving. Sometimes a player would excel in one format over the other, but for the most part, the best were the best. On the women’s side, Martina Navratilova, Billie Jean King, Serena Williams, and Margaret Court all reached major title hauls in double digits in both singles and doubles. Roy Emerson, who was long the all-time leader in major men’s singles titles with 12 until his record was broken by Pete Sampras in 2000, also won 16 major men’s doubles titles. John McEnroe won nine major titles in men’s doubles to complement his seven major singles titles.

With singles becoming an outsized priority and requiring increasingly prohibitive focus, that duality no longer exists, and doubles without singles stars has become a less attractive product as a result.

The current population of doubles specialists—despite the incredible opportunity for exposure they now have from almost every doubles match now being available to watch on tennis streaming platforms—has not grown the popularity of doubles. Singles remains the only avenue in tennis for global stars to be born and for fans to become attached to players. No doubles specialists this century, except for the Bryan Brothers, have come remotely close to making themselves stars with any worldwide marquee value.2

Big Change in the Big Apple:

The U.S. Open, to its credit, recognized this reality. Rather than mindlessly running another irrelevant, dead-weight mixed doubles competition this year, the U.S. Open chose to breathe life into the format with a radical revamp, as they officially announced Tuesday after weeks of leaks:

“TENNIS’ BIGGEST STARS WILL HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY TO COMPETE FOR A COVETED MIXED DOUBLES GRAND SLAM TITLE, A MULTI-MILLION DOLLAR PURSE AND A $1 MILLION PRIZE.”

Instead of taking place during the final week of the tournament, when all the biggest stars are laser-focused on late-round singles matches (or already on flights home if they’ve lost), the mixed doubles competition will be an amuse-bouche before the main draw, taking place on the Tuesday and Wednesday before the tournament. Instead of being shunted to the outer courts, mixed doubles matches will be held exclusively on Arthur Ashe Stadium and Louis Armstrong Stadium. And instead of mixed doubles champions being paid peanuts, there will be $1 million for the winning pair, and an overall prize purse in the millions.

To make participation less daunting on the eve of a major, matches will be streamlined into best-of-three-set matches with short sets to four games, no-ad scoring, tiebreakers at 4-all and a 10-point match tiebreak in lieu of a third set. The final will be a more standard length mixed doubles match, best-of-three set match with sets to six games, no-ad scoring, tiebreakers at 6-all, and a 10-point match tiebreaker in lieu of a third set.

The biggest change: Instead of being contested almost entirely by doubles specialists who haven’t captured the public’s attention or imagination in previous editions, the draw will largely be filled with singles stars. The U.S. Open mixed doubles field will be made up of 16 pairs, with eight entries based on singles rankings only—rather than singles or doubles rankings as it was previously—and the other eight entries being wild-card teams.

Taylor Fritz and Jessica Pegula, the two runners-up in the U.S. Open singles draws last year, both indicated a desire to participate in the U.S. Open’s press release on the new reformatting. The biggest obstacle to star participation in mixed doubles now might be the overflow of the preceding Cincinnati tournament, with its unnecessary Monday final ending just one day before the relocated mixed doubles event.

(Tumaini Carayol and I discussed the schedule and mixed doubles changes starting about 28 minutes into the latest episode of No Challenges Remaining)

The complaints from traditionalists—and doubles specialists outraged at being shut out—have been predictable and, I think, easily shot down. Most prominently, the reigning U.S. Open mixed doubles champion pair of Andrea Vavassori and Sara Errani put out a statement calling the new format a “pseudo-exhibition.” But surely mixed doubles at majors, by not giving ranking points, already met the most common definition of an exhibition event? Although if major mixed doubles was an exhibition event before, admittedly, it was a bad one: Exhibition events are designed to draw crowds and sell tickets to see stars, and those star players then collect big paychecks for participating; mixed doubles at majors hasn’t met any of those appealing criteria for a long time. If mixed doubles has become a bona fide “exhibition” event with this change, that’s an upgrade from the afterthought it was before.

Vavassori and Errani also cited “tradition and history” as reasons for keeping things the old way. But the meaningful “tradition” of mixed doubles, historically, wasn’t to assure that no one gave a shit about it, which is all a lack of change would accomplish with the current trajectory of the category. To be more blunt, the idea that a mixed doubles title was something worthy of the “Grand Slam” label in its recent iterations has seemed increasingly hollow as the mixed doubles fields grew weaker and more anonymous, and as the pay gulf became so stark as a result.

There’s been a lot of pity for doubles specialists on social media since this announcement—much of it from the doubles specialists themselves—and I don’t think that will prove helpful to their cause. What would be helpful, I think, is for this to be a wake-up call. If this comes off as harsh toward doubles specialists, it’s meant to: I think they’ve had their chance to prove themselves as attractions for years now—again, especially with every doubles match now fully produced and available to stream and to clip on social media—and they’ve consistently shown that they cannot. The idea that the U.S. Open should maintain a system of handouts or charity for doubles specialists rather than revamp the mixed doubles event into something worthy of being showcased at a Grand Slam is unconvincing, especially because the prize money for the event that they’re whining about missing out on was so paltry compared with the more-than-quadrupled amount the tournament thinks mixed doubles can be worth now.

My hope is that the U.S. Open deciding to make mixed doubles into something that people will watch and care about—and how they determined the best way to do that—will light a fire under the complacency of doubles specialists about their places in the business model of the sport, if they care enough to fight for it. And even without learning to win singles matches, there’s still a way into the mixed doubles draw: They can learn to become entertaining, compelling, and popular enough in the next few months to convince U.S. Open organizers that they should be awarded some of those wild-card entry spots.

If they can do that, the sport will be stronger for it, and everyone will win big.

A version of this story also appears at The Second Serve, a weekly newsletter covering pro tennis and the fashion and culture adjacent to it. Sign up here!

The champions were the Australian wildcard pairing of Olivia Gadecki and John Peers; Gadecki banked far more prize money for losing 6-1, 6-1 in the first round of the singles draw than she did for winning the mixed doubles tournament.

A doubles specialist can gain some recognition in their home country if it lacks top singles players, as has happened in India, Colombia, and Brazil in recent decades, otherwise doubles specialization insures relative anonymity.

Ohhhhhhh Ben!! How can you do us fans (and the doubles specialists) dirty like this?? Maybe go over to r/tennis on Reddit and see the HOWLS of protest in several threads against the US Open’s decision? We all *hate* it, and you’re welcome to peruse the many comments to find out why!

I'm for the scheduling change along with the focus on singles players, but I do NOT like the 4 game set change. Is playing an extra 2-4 games really that hard? I'm not really a fan of no-ad scoring either, but I can live with it. I don't mind the 10 point 3rd set tiebreaker either. But 4 game sets? Nope.

Ben wrote, "If this comes off as harsh toward doubles specialists, it’s meant to: I think they’ve had their chance to prove themselves as attractions for years now." To me, it's a chicken and egg situation. How do we expect people to care about doubles teams if doubles matches are almost never broadcast by mainstream media like Tennis Chanel and ESPN? But how do we expect those channels to broadcast doubles when people don't care about the doubles specialists? (To me, the streaming options don't matter. Diehard fans will find those. People who we hope to grow the sport for won't.) I don't see this situation being resolved.

Note: Some of the best professional tennis matches I've seen have been doubles matches featuring doubles specialists. But I can see why the casual fan might not be interested.